Betting on The Web

NOTE: this is a Talk I gave at the ColdFront 2017 conference in Copenhagen in which I make the argument for betting on the web and building PWAs. It's included here for those who still need convincing that building for The Web is a wise choice

I’m not going to tell you what to do. Instead, I’m going to explain why I’ve chosen to bet my whole career on this crazy Web thing. "Betting" sounds a bit haphazard, it’s more calculated than that. It would probably be better described as "investing."

Investing what? Our time and attention.

Many of us only have maybe 6 or so really productive hours per day when we’re capable of being super focused and doing our absolute best work. So how we chose to invest that very limited time is kind of a big deal. Even though I really enjoy programming I rarely do it aimlessly just for the pure joy of it. Ultimately, I’m investing that productive time expecting to get some kind of return even if it’s just mastering something or solving a difficult problem.

"So what, what’s your point?"

More than most of us realize we are constantly investing

Sure, someone may be paying for our time directly but there’s more to it than just trading hours for money. In the long run, what we chose to invest our professional efforts into has other effects:

1. Building Expertise: We learn as we work and gain valuable experience in the technologies and platform we’re investing in. That expertise impacts our future earning potential and the types of products we’re capable of building.

2. Building Equity: Hopefully we’re generating equity and adding value to whatever product we’re building.

3. Shaping tomorrow’s job market: We’re building tomorrow’s legacy code today™. Today’s new hotness is tomorrow’s maintenance burden. In many cases, the people that initially build a product or service are not the ones that ultimately maintain it. This means the technology choices we make when building a new product or service, determine whether or not there will be jobs later that require expertise in that particular platform/technology. So, those tech choices literally shape tomorrow’s job market!

4. Increasing the body of knowledge: As developers, we’re pretty good at sharing what we learn. We blog, we "Stack-Overflow", etc. These things all contribute to the corpus of knowledge available about that given platform which adds significant value by making it easier/faster for others to build things using these tools.

5. Open Source: We solve problems and share our work. When lots of developers do this it adds tremendous value to the technologies and platforms these tools are for. The sheer volume of work that we don’t have to do because we can use someone else’s library that already does it is mind-boggling. Millions and millions of hours of development work are available to us for free with a simple npm install.

6. Building apps for users on that platform: Last but not least, without apps there is no platform. By making more software available to end users, we’re contributing significant value to the platforms that run our apps.

Looking at that list, the last four items are not about us at all. They represent other significant long-term impacts.

We often have a broader impact than we realize

We’re not just investing time into a job, we're also shaping the platform, community, and technologies we use.

We’re going to come back to this, but hopefully, recognizing that greater impact can help us make better investments.

With all investing comes risk

We can’t talk about investing without talking about risk. So what are some of the potential risks?

Are we building for the right platform?

Platform stability is indeed A Thing™. Just ask a Flash developer, Windows Phone developer, or Blackberry developer. Platforms can go away.

If we look at those three platforms, what do they have in common? They’re closed platforms. What I mean is there’s a single controlling interest. When you build for them, you’re building for a specific operating system and coding against a particular implementation as opposed to coding against a set of open standards. You could argue, that at least to some degree, Flash died because of its "closed-ness". Regardless, one thing is clear from a risk mitigation perspective: open is better than closed.

the Web is incredibly open. It would be quite difficult for any one entity to kill it off.

Now, for Windows Phone/Blackberry it failed due to a lack of interested users... or was it lack of interested developers??

Maybe if Ballmer ☝️ has just yelled "developers" one more time we’d all have Windows Phones in our pockets right now 😜.

From a risk mitigation perspective, two things are clear with regard to platform stability:

- Having many users is better than having few users

- Having more developers building for the platform is better than having few developers

There is no bigger more popular open platform than the Web

Are we building the right software?

Many of us are building apps. Well, we used to build "applications" but that wasn’t nearly cool enough. So now we build "apps" instead 😎.

What does "app" mean to a user? This is important because I think it’s changed a bit over the years. To a user, I would suggest it basically means: "a thing I put on my phone."

But for our purposes, I want to get a bit more specific. I’d propose that an app is really:

- An "ad hoc" user interface

- That is local(ish) to the device

The term "ad hoc" is Latin and translates to "for this". This actually matches pretty closely with what Apple’s marketing campaigns have been teaching the masses:

There’s an app for that

– Apple

The point is it helps you do something. The emphasis is on action. I happen to think this is largely the difference between a "site" and an "app". A news site, for example, has articles that are resources in and of themselves. Where a news app is software that runs on the device that helps you consume news articles.

Another way to put it would be that site is more like a book, while an app is a tool.

Should we be building apps at all?!

Remember when chatbots were supposed to take over the world? Or perhaps we’ll all be walking around with augmented reality glasses and that’s how we’ll interact with the world?

I’ve heard it said that "the future app is no app" and virtual assistants will take over everything.

I’ve had one of these sitting in my living room for a couple of years, but I find it all but useless. It’s just a nice Bluetooth speaker that I can yell at to play me music.

But I find it very interesting that:

Even Alexa has an app!

Why? Because there’s no screen! As it turns out these "ad hoc visual interfaces" are extremely efficient.

Sure, I can yell out "Alexa, what’s the weather going to be like today" and I’ll hear a reply with high and low and whether it’s cloudy, rainy, or sunny. But in that same amount of time, I can pull my phone out tap the weather app and before Alexa can finish telling me those 3 pieces of data, I can visually scan the entire week’s worth of data, air quality, sunrise/sunset times, etc. It’s just so much more efficient as a mechanism for consuming this type of data.

As a result of that natural efficiency, I believe that having a visual interface is going to continue to be useful for all sorts of things for a long time to come.

That’s not to say virtual assistants aren’t useful! Google Assistant on my Pixel is quite useful in part because it can show me answers and can tolerate vagueness in a way that an app with a fixed set of buttons never could.

But, as is so often the case with new useful tech, rarely does it completely replace everything that came before it, instead, it augments what we already have.

If apps are so great why are we so "apped out"?

How do we explain that supposed efficiency when there’s data like this?

- 65% of smartphone users download zero apps per month

- More than 75% of app downloads open an app once and never come back

I think to answer that we have to really look at what isn’t working well.

What sucks about apps?

- Downloading them certainly sucks. No one wants to open an app store, search for the app they’re trying to find, then wait to download the huge file. These days a 50mb app is pretty small. Facebook for iOS 346MB, Twitter iOS 212MB.

- Updating them sucks. Every night I plug in my phone I download a whole slew of app updates that I, as a user, could not possibly care less about. In addition, many of these apps are things I installed once and will never open again, ever!. I’d love to know the global stats on how much bandwidth has been wasted on app updates for apps that were never opened again.

- Managing them sucks. Sure, when I first got an iPhone ages ago and could first download apps my home screen was impeccable. Then when we got folders!! Wow... what an amazing development! Now I could finally put all those pesky uninstallable Apple apps in a folder called "💩" and pretend they didn’t exist. But now, my home screen is a bit of a disaster. Sitting there dragging apps around is not my idea of a good time. So eventually things get all cluttered up again.

The thing I’ve come to realize is this:

We don’t care how they got there. We only care that they’re there when we need them.

For example, I love to go mountain biking and I enjoy tracking my rides with an app called Strava. I get all geared up for my ride, get on my bike and then go, "Oh right, gotta start Strava." So I pull out my phone with my gloves on and go: "Ok Google, open Strava".

I could not care less about where that app was or where it came from when I said that.

I don’t care if it was already installed, I don’t care if it never existed on my home screen, or if it was generated out of thin air on the spot.

Context is everything!

If I’m at a parking meter, I want the app for that. If I’m visiting Portland, I want their public transit app.

But I certainly do not want it as soon as I’ve left.

If I’m at a conference, I might want a conference app to see the schedule, post questions to speakers, or whatnot. But wow, talk about something that quickly becomes worthless as soon as that conference is over!

As it turns out the more "ad hoc" these things are, the better! The more disposable and re-inflatable the better!

Which also reminds me of something that I feel like we often forget. We always assume people want our shiny apps and we measure things like "engagement" and "time spent in the app" when really, and there certainly are exceptions to this such as apps that are essentially entertainment, but often...

People don’t want to use your app. They want to be done using your app.

Enter PWAs

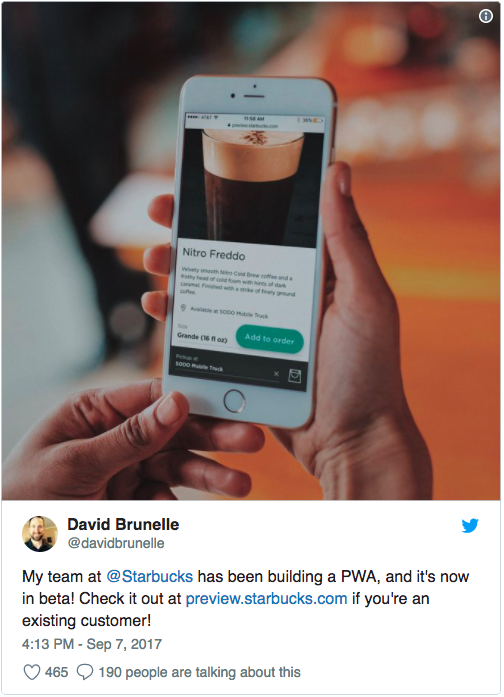

I’ve been contracting with Starbucks for the past 18 months. They’ve taken on the ambitious project of essentially re-building a lot of their web stuff in Node.js and React. One of the things I’ve helped them with (and pushed hard for) was to build a PWA (Progressive Web App) that could provide similar functionality as their native apps. Coincidentally it was launched today: https://app.starbucks.com!

This gives is a nice real-world example:

- Starbucks iOS: 146MB

- Starbucks PWA: ~600KB

The point is there’s a tremendous size difference.

It’s 0.4% of the size. To put it differently, I could download the PWA 243 times in the same amount of time it would take to download the iOS app. Then, of course on iOS, it then also still has to install and boot up!

Personally, I’d have loved it if the app ended up even smaller and there are plans to shrink it further. But even still, they’re not even on the same planet in terms of file-size!

Market forces are strongly aligned with PWAs here:

- Few app downloads

- User acquisition is hard

- User acquisition is expensive

If the goal is to get people to sign up for the rewards program, that type of size difference could very well make the difference of getting someone signed up and using the app experience (via PWA) by the time they reach the front of the line at Starbucks or not.

User acquisition is hard enough already, the more time and barriers that can be removed from that process, the better.

Quick PWA primer

As mentioned, PWA stands for "Progressive Web Apps" or, as I like to call them: "Web Apps" 😄

Personally, I’ve been trying to build what a user would define as an "app" with web technology for years. But until PWAs came along, as hard as we tried, you couldn’t quite build a real app with just web tech. Honestly, I kinda hate myself for saying that, but in terms of something that a user would understand as an "app" I’m afraid that statement has probably true until very recently.

So what’s a PWA? As one of its primary contributors put it:

It’s just a website that took all the right vitamins.

– Alex Russell

It involves a few specific technologies, namely:

- Service Worker. Which enable true reliability on the web. What I mean by that is I can build an app that as long as you loaded it while you were online, from then on it will always open, even if you’re not. This puts it on equal footing with other apps.

- HTTPS. Requires encrypted connections

- Web App Manifest. A simple JSON file that describes your application. What icons to use is someone adds it to their home screen, what its name is, etc.

There are plenty of other resources about PWAs on the web. The point for my purposes is:

It is now possible to build PWAs that are indistinguishable from their native counterparts

They can be up and running in a fraction of the time whether or not they were already "installed" and unlike "apps" can be saved as an app on the device at the user’s discretion!

Essentially they’re really great for creating "ad hoc" experiences that can be "cold started" on a whim nearly as fast as if it were already installed.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again:

PWAs are the biggest thing to happen to the mobile web since the iPhone.

– Um... that was me

Let’s talk Internet of things

I happen to think that PWAs + IoT = ✨ MAGIC ✨. As several smart folks have pointed out.

The one-app-per-device approach to smart devices probably isn’t particularly smart.

It doesn’t scale well and it completely fails in terms of "ad hoc"-ness. Sure, if I have a Nest thermostat and Phillips Hue light bulbs, it’s reasonable to have two apps installed. But even that sucks as soon as I want someone else to be able to use control them. If I just let you into my house, trust me... I’m perfectly happy to let you flip a light switch, you’re in my house, after all. But for the vast majority of these things there’s no concept of "nearby apps" and, it’s silly for my guest (or a house-sitter) to download an app they don’t actually want, just so I can let them control my lights.

The whole "nearby apps" thing has so many uses:

- thermostat

- lights

- locks

- garage doors

- parking meter

- setting refrigerator temp

- conference apps

Today there are lots of new capabilities being added to the web to enable web apps to interact with physical devices in the real world. Things like WebUSB, WebBluetooth, WebNFC, and efforts like Physical Web. Even for things like Augmented (and Virtual) reality, the idea of the items we want to interact with having URLs makes so much sense and I can’t imagine a better, more flexible use of those URLs than for them to point to a PWA that lets you interact with that device!

Forward-looking statements...

I’ve been talking about all this in terms of investing. If you’ve ever read any company statement that discusses the future you always see this line explaining that things that are about to be discussed contain "forward-looking statements" that may or may not ultimately happen.

So, here are my forward-looking statements.

1. PWA-only startups

Given the cost (and challenge) of user-acquisition and the quality of app you can build with PWAs these days, I feel like this is inevitable. If you’re trying to get something off the ground, it just isn’t very efficient to spin up three whole teams to build for iOS, Android, and the Web.

2. PWAs listed in App Stores

So, there’s a problem with "web only" which is that for the good part of a decade we’ve been training users to look for apps in the app store for their given platform. So if you’re already a recognized brand, especially if you already have a native app that you’re trying to replace, it simply isn’t smart for you not to exist in the app stores.

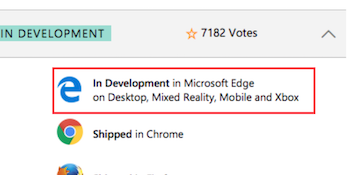

So, some of this isn’t all that "forward-looking" as it turns out Microsoft has already committed to listing PWAs in the Windows Store, more than once!

They haven’t even finished implementing Service Worker in Edge yet! But they’re already committing hard to PWAs. In addition to the blog post linked above, one of their lead Developer Relations folks, Aaron Gustafson just wrote an article for A List Apart telling everyone to build PWAs.

But if you think about it from their perspective, of course, they should do that! As I said earlier they’ve struggled to attract developers to build for their mobile phones. In fact, they’ve at times paid companies to write apps for them simply to make sure apps exist so that users will be able to have apps they want when using a Windows Phone. Remember how I said developer time is a scarce resource and without apps, the platform is worthless? So of course they should add first class support for PWAs. If you build a PWA like a lot of folks are doing then TADA!!! 🎉 You just made a Windows/Windows Phone app!

I’m of the opinion that the writing is on the wall for Google to do the same thing. It’s pure speculation, but it certainly seems like they are taking steps that suggest they may be planning on listing PWAs too. Namely that the Chrome folks recently shipped a feature referred to as "WebAPKs" for Chrome stable on Android (yep, everyone). In the past I’ve explained in more detail why I think this is a big deal. But a shorter version would be that before this change, sure you could save a PWA to your home screen... But, in reality, it was actually a glorified bookmark. That’s what changes with WebAPKs. Instead, when you add a PWA to your home screen it generates and "side loads" an actual .apk file on the fly. This allows that PWA to enjoy some privileges that were simply impossible until the operating system recognized it as "an app." For example:

- You can now mute push notifications for a specific PWA without muting it for all of Chrome.

- The PWA is listed in the "app tray" that shows all installed apps (previously it was just the home screen).

- You can see power usage, and permissions granted to the PWA just like any other app.

- The app developer can now update the icon for the app by publishing an update to the app manifest. Before, there was no way to update the icon once it had been added.

- And a slew of other similar benefits...

If you’ve ever installed an Android app from a source other than the Play Store (or carriers/OEMs store) you know that you have to flip a switch in settings to allow installs from "untrusted sources". So, how then, you might ask, can they generate and install an actual .apk file for a PWA without requiring that you change that setting? As it turns out the answer is quite simple: Use a trusted source!

As it turns out WebAPKs are managed through Google Play Services!

I’m no rocket scientist, but based on their natural business alignment with the web, their promotion of PWAs, the lengths they’ve gone to grant PWAs equal status on the operating system as native apps, it only seems natural that they’d eventually list them in the store.

Additionally, if Google did start listing PWAs in the Play Store both them and Microsoft would be doing it leaving Apple sticking out like a sore thumb and looking like the laggard. Essentially, app developers would be able to target a massive number of users on a range of platforms with a single well-built PWA. But, just like developers grew to despise IE for not keeping up with the times and forcing them to jump through extra hoops to support it, the same thing would happen here. Apple does not want to be the next IE and I’ve already seen many prominent developers suggesting they already are.

Which bring us to another forward-looking statement:

3. PWAs on iOS

Just a few weeks ago the Safari folks announced that Service Worker is now officially under development.

4. PWAs everywhere

I really think we’ll start seeing them everywhere:

- Inside VR/AR/MR experiences

- Inside chatbots (again, pulling up an ad-hoc interface is so much more efficient).

- Inside Xbox?!

As it turns out, if you look at Microsoft’s status page for Edge about Service Worker you see this:

I hinted at this already, but I also think PWAs pair very nicely with virtual assistants being able to pull up a PWA on a whim without requiring it to already be installed would add tremendous power to the virtual assistant. Incidentally, this also becomes easier if there’s a known "registered" name of a PWA listed in an app store.

Some other fun use cases:

- Apparently the new digital menu displays in McDonald’s Restaurants (at least in the U.S.) are actually a web app built with Polymer (source). I don’t know if there’s a Service Worker or not, but it would make sense for there to be.

- Sports scoreboards!? I’m an independent consultant, and someone approached me about potentially using a set of TVs and web apps to build a scorekeeping system at an arena. Point is, there are so many cool examples!

The web really is the universal platform!

For those who think PWAs are just a Google thing

First off, I’m pretty sure Microsoft, Opera, Firefox, and Samsung folks would want to punch you for that. It simply isn’t true and increasingly we’re seeing a lot more compatibility efforts between browser vendors.

For example: check out the Web Platform Tests which is essentially Continuous Integration for web features that are run against new releases of major browsers. Some folks will recall that when Apple first claimed they implemented IndexedDb in Safari, the version they shipped was essentially unusable because it had major shortcomings and bugs.

Now, with the Web Platform Tests, you can drill into these features (to quite some detail) and see whether a given browser passes or fails. No more claiming "we shipped!" but not actually shipping.

What about feature "x" on platform "y" that we need?

It could well be that you have a need that isn’t yet covered by the web platform. In reality, that list is getting shorter and shorter, also... HAVE YOU ASKED?! Despite what it may feel like, browser vendors eagerly want to know what you’re trying to do that you can’t. If there are missing features, be loud, be nice, but from my experience, it’s worth making your desires known.

Also, it doesn’t take much to wrap a web view and add hooks into the native OS that your JavaScript can call to do things that aren’t quite possible yet.

But that also brings me to another point, in terms of investing, as the world’s greatest hockey player said:

Skate to where the puck is going, not where it has been.

– Wayne Gretzky

Based on what I’ve outlined thus far, it could be riskier to build an entire application for a whole other platform that you ultimately may not need than to at least exhaust your options seeing what you can do with the Web first.

So to line ’em up in terms of PWA support:

- Chrome: yup

- Firefox: yup

- Opera: yup

- Samsung Internet (the 3rd largest browser surprise!): yup

- Microsoft: huge public commitment

- Safari: at least implementing Service Worker

Ask them to add your feature!

Sure, it may not happen, it may take a long time but at least try. Remember, developers have a lot more influence over platforms than we typically realize. Make. your. voice. heard.

Side note about React-Native/Expo

These projects are run by awesome people, the tech is incredibly impressive. If you’re Facebook and you’re trying to consolidate your development efforts, for the same basic reasons as for why it makes sense for them to create their own VM for running PHP. They have realities to deal with at a scale that most of us will never have to deal with. Personally, I’m not Facebook.

As a side note, I find it interesting that building native apps and having as many people do that as possible, plays nicely into their advertising competition with Google.

It just so happens that Google is well positioned to capitalize off of people using the Web. Inversely, I’m fairly certain Facebook wouldn’t mind that ad revenue not going Google. Facebook, seemingly would much rather be your web, that be part of the Web.

Anyway, all that aside, for me it’s also about investing well.

By building a native app you’re volunteering for a 30% app-store tax. Plus, like we covered earlier odds are that no one wants to go download your app. Also, though it seems incredibly unlikely, I feel compelled to point out that in terms of "openness" Apple’s App Store is very clearly anything but that. Apple could decide one day that they really don’t like how it’s possible to essentially circumvent their normal update/review process when you use Expo. One day they could just decide to reject all React Native apps. I really don’t think they would because of the uproar it would cause. I’m simply pointing out that it’s their platform and they would have every right to do so.

So is it all about investing for your own gain?

So far, I’ve presented all this from a kind of a cold, heartless investor perspective: getting the most for your time.

But, that’s not the whole story, is it?

Life isn’t all about me. Life isn’t all about us.

I want to invest in platforms that increase opportunities for others. Personally, I really hope the next friggin’ Mark Zuckerburg isn’t an ivy-league dude. Wouldn’t it be amazing if instead the next huge success was, I don’t know, perhaps a young woman in Nairobi or something? The thing is, if owning an iPhone is a prerequisite for building apps, it dramatically decreases the odds of something like that happening. I feel like the Web really is the closest thing we have to a level playing field.

I want to invest in and improve that platform!

This quote really struck me and has stayed with me when thinking about these things:

If you’re the kind of person who tends to succeed in what you start,

changing what you start could be the most extraordinary thing you could do.

– Anand Giridharadas

Thanks for your valuable attention ❤️. I’ve presented the facts as I see them and I’ve done my best not to "should on you."

Ultimately though, no matter how prepared we are or how much research we’ve done; investing is always a bit of a gamble.

So I guess the only thing left to say is:

I’m all in.